One of my favorite CEO's of all time is A.G. Lafley,

who recently stepped down after running Procter & Gamble for a

decade. There are many things I admire about A.G. His modesty and

ability to listen — and I mean really listen, not just pretend —

impressed me when I first met him in 2000, and when I spoke with again

last year I found him unchanged, even after all the praise he has

received.

But perhaps the thing I admire most about A.G. is that, in contrast

to so many other CEOs (and management gurus and authors) he doesn't

pretend for a second that he discovered a new way to manage, or that his

success resulted from any mysterious and complicated methods. One of

his catchphrases is "keep it Sesame Street simple,"

and indeed he spent a lot of time reminding people of simple truths,

like "the consumer is boss." He often exhorted his managers to focus on

what happens at "two moments of truth": when the customer encounters the

P&G product in a retail setting; and when they actually use the

product. Hammering on such old and simple themes, A.G. brought P&G back from

the dark period it was in when he took over in 2000. The norms and

example he set, plus the people he developed, are still enabling P&G

to be a great company.

Cries for the reinvention of management and claims that we have to discard old models are

made by every generation of gurus. But really, the ideas that work

aren't that complicated, and most of what is called new is really the

same old wine in relabeled bottles. If you want to read a great book on

this point, check out Robert Eccles' and Nitin Nohria's Beyond The Hype.

When I read it for the first time, I realized that a big reason every

generation thinks that its solutions are new is because it thinks its challenges are

brand new. People can't quite bring themselves to believe that managers

of the past faced remarkably similar problems, found frustration and

satisfaction in similar sources, and came up with similar solutions.

Just as teenagers discover sex and can't imagine that the fundamentals

were the same for their parents, managers are convinced they are

encountering forces and feelings that haven't been seen before. And

management theorists do little to disabuse them of that notion.

To this point, some years back when Jeff Pfeffer and I were writing our book on evidence-based management, I wrote Stanford's James March (arguably

the most respected living organizational theorist) to ask him for

examples of truly breakthrough ideas. His response was "Most claims of

originality are testimony to ignorance and most claims of magic are

testimonial to hubris." I promptly repurposed this into Sutton's law:

"If you think that you have a new idea, you are wrong. Someone probably

already had it. This idea isn't original either; I stole it from

someone else."

I am not denying that bosses work in different environments these

days — the computer revolution and global nature of business have

reshaped organizations, for example — but the fundamentals of being a

good boss have changed a lot less than people claim. While writing Good Boss, Bad Boss I

had occasion to compare studies conducted in every decade from 1940's

through the 2000's, and they yielded very similar advice. Even studying

pre-industrial people, anthropologists have concluded that the best

leaders were competent, caring, and benevolent — and leaders who failed

in any of these areas put their people at risk and had a hard time

getting or keeping leadership positions. Research on the modern

workplace, too, leads me to conclude that the best bosses strike a

healthy balance between promoting performance and protecting their

people's dignity and well-being. I am using different language, but it

seems to me that what constitutes a decent boss hasn't really changed

much in thousands of years.

Unfortunately, the formula seems to be easier to state than to put into

action. Another consistent finding over time is that, if you're a

typical employee, your immediate supervisor is the most stressful part

of your job.

The lesson from all this is that old, proven, simple, and obvious ideas

on how to manage may be dull — and some may be outmoded now and then —

but they are your best hope if you want to be a good boss.

But now, let me complicate my message just a bit, by recalling my own reaction to Jim Collins' blockbuster Good to Great (read more here).

The hallmarks of good management and leadership Collins identified were

consistent with much prior research — much of it more rigorous than his

own (and he mentioned almost none of it). But there's something so

compelling about his telling of the story, and I think that has

everything to do with his own sense of discovery. Maybe, as with

teenagers discovering sex, management theorists — and managers — bring

more passion to the experience when they arrive at the basics

themselves.

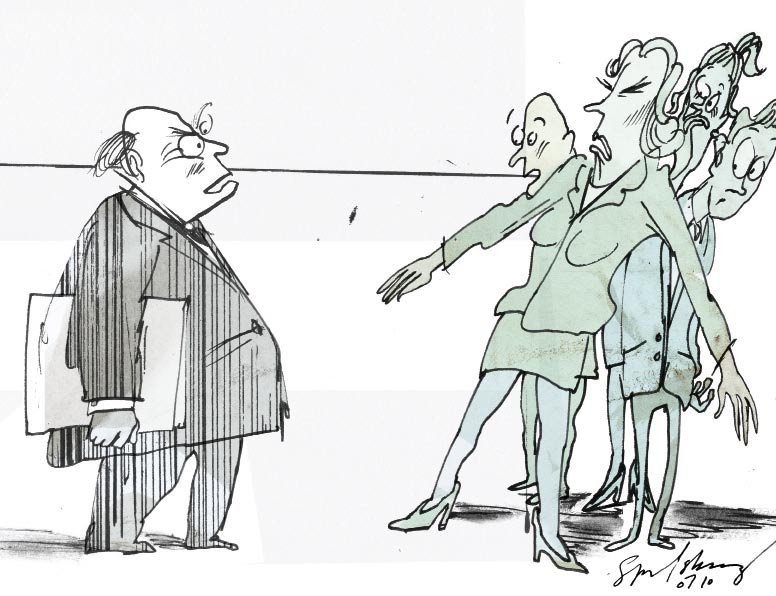

P.S. This post represents a persistent theme in my writing, especially with Jeff Pfeffer, which I revisited and developed a bit more for the list 12 Things Good Bosses Believe that I am rolling out over at HBR, where it first appeared as What Every New Generation Of Bosses Have To Learn. Indeed, if you look at the big business story this week, that Mark Hurd was canned by HP for behavior connected to a sexual harassment claim, I don't think that we need any newfangled theories to explain his behavior — a Yiddish expression that has been around for hundreds of year captures it all.