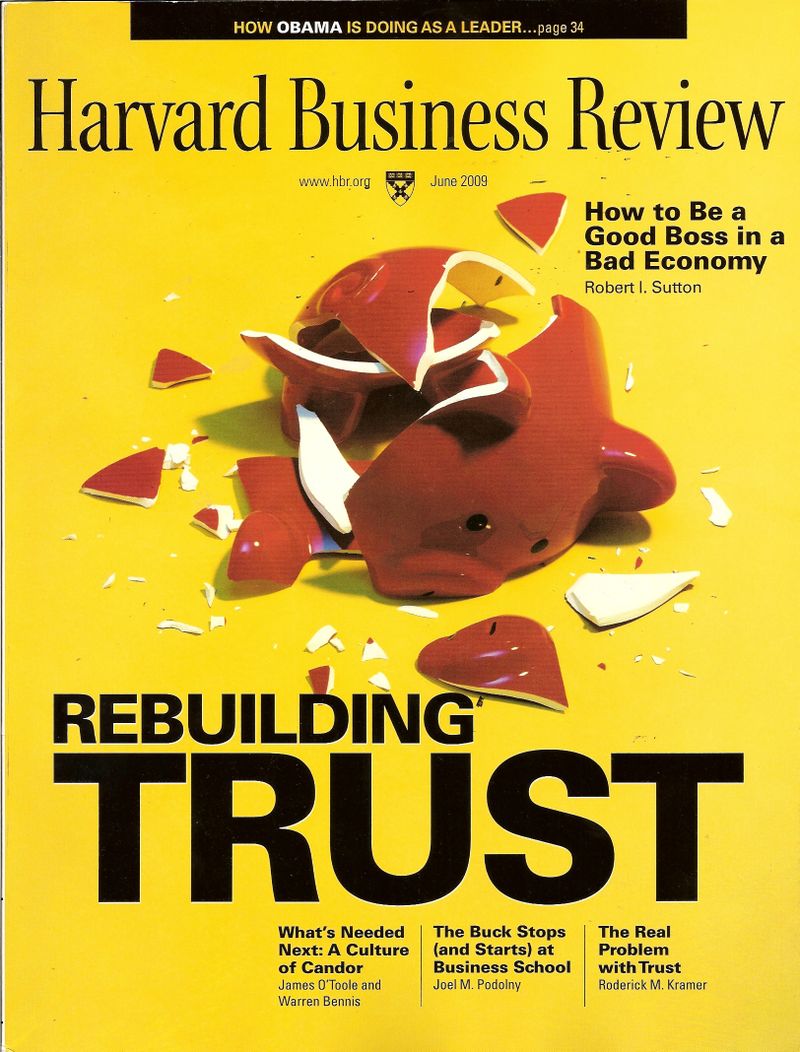

The folks at Harvard Business Review told me that "How to Be a Good Boss in a Bad Economy" would be "sort of" the lead article in the June issue. I am not entirely sure what that means, but I thank them for making it so prominent on their cover. My initial reaction to the cover was to flinch as it is disconcerting, but as one CEO I know said, unfortunately, it is spot on because it reflects how so many people are feeling during these tough times. I already blogged a bit about some of the themes developed in the article in Of Baboons and Bosses, and will put-up more thoughts over the next couple weeks. Also, stay tuned because HBR will be sending me a link, I think next week, so I will be able to give away 100 copies, which I will do here as soon as I can. I haven't seen the issue, but I am a huge fan of both Rod Kramer, Joel Podolny, James O'Toole, and of course, the famous and charming Warren Bennis. Also, I note that all four five of us live in California. HBR has been accused of being overly disposed to publish articles from Harvard Business School faculty — perhaps they also have a pro-California bias! Although Joel's last job was being a dean Yale, he is now at Apple, so is back in California.

Category: Bosses

-

“How to Be a Good Boss in a Bad Economy” Featured in the New HBR

-

Of Baboons and Bosses

I wrote a Harvard Business Review article that is hitting the stands (and I guess the web) next week called "How to Be a Good Boss in a Bad Economy." One of the points I make is that bosses aren't always sufficiently aware of how closely their subordinates are scrutinizing and trying to make sense of their behavior, and that people watch their bosses every move especially closely when fear is in the air, such is during the tough times so many organizations are suffering now. (see this "Interesting Shoes" post for a great example).

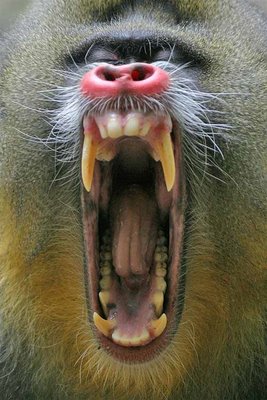

In the HBR article, I suggest that hyperfocus on the creature at the top of the pecking order is evident in other primates as well. And I quote research suggesting that in baboon troops, the typical members looks at the the alpha make every 20 to 30 seconds to see what he is doing. I was exchanging emails with the HBR editor I worked with on the piece, the amazing Julia Kirby, and she suggested that I put up a post to give people a bit more information about the source of this tidbit.

It comes from an article by anthropologist Lionel Tiger and here is the key excerpt. Note the key insight is pretty fascinating:"Chance's argument is that a major, if not the most

significant, characteristic of political interaction involves who looks at

whom." Start thinking about when you go to your next meeting or when you observe your next meeting — it is an insight with hundreds of implications, as it reveals the power and communication patterns, and helps explain why, although a group of seven or eight people may all seem to have been at the same meeting, in essence, each saw and heard completely different things. This quote below is pretty academic, but most academic writing isn't nearly this insightful or intriguing:A proposition by Chance

about attention structure requires explication; it may well be one of the few

original and useful basic ideas to be developed about political systems in a

very long time (25). Chance's argument is that a major, if not the most

significant, characteristic of political interaction involves who looks at

whom. The suggestion is that the chief functional difference between the leader

and the follower is that the followers look at the leader; the opposite does

not happen as regularly or intensely. Chance's proposition refers primarily to

primates and applies most obviously to terrestrial animals, such as the

baboons, for whom it clearly would be in the interest of survival to centralize

information-like that coming from suba-dult males at the more dangerous and

revealing periphery of the troop-and to pay close, united regard to the

dominant male's signals. This is a deceptively simple idea; its analytical

virtue is that it crosscuts a host of structural factors in primate systems and

attends to very obvious behavioral ones. For example, in a baboon troop all

For example, in a baboon troop all

animals will glance at the leader every 20 or 30 seconds and return to whatever

they are doing. The leader is, of course, normally found at the center of the

group, and almost by definition where the leader is constitutes the group's

center (except during movement). The forces of interaction then, in common

with the general importance of gregariousness in such animals, render these

societies centripetal, as Chance calls them, as opposed to centrifugal. The

tension between escape and staying and the problems of status and hierarchy are

articulated in a relatively elastic but nonetheless definable web which

constitutes the boundary between one primate group and another.I guess that The Office's Michael Scott and that snarling baboon might have more in common than might appear at first. Indeed, that TV show captures pretty well how closely his people watch him, and how oblivious he can be to their actions, reactions, and needs. As the saying goes, one of the reasons that show is so funny is because it is so true.

P.S. The excerpt is from: "Dominance in Human Societies" Author(s): Lionel Tiger

Source: Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, Vol. 1 (1970), pp. 287-306

Published by: Annual Reviews. -

Kelley Eskridge’s Wise Advice on Running Meetings

The comments and questions generated by my post last week on Do You End Meetings on Time? are consistently wise and thoughtful, but I wanted to highlight the one by Kelley Eskridge in particular. It isn't just about ending meetings, it is about how to run a great meeting in general. I also suggest that you check out Kelley's website and blog. Her website is for her company, Humans at Work. You can see why she knows so much about running groups, as she does this for a living. The most amazing thing about her company website is that — although she will charge you to do it herself — she provides detailed advice about how to use her group intervention method yourself for free… now that is rare. I can't imagine Bain, BCG, or McKinsey doing quite the same thing!

Also, as I read her blog, I also learned Kelley has published a well-reviewed novel and many stories. Here novel, Solitaire, is being developed into a film. I guess that explains why her blog is so well-written, as is this lovely advice below on meetings. I especially like her advice about how a combination of rules, process skills, and a bit of polite courage can be used to gently tamp down destructive and overbearing team members:

One tool that has always helped me facilitate meetings — my own, and those fun times when I am the facilitator for the 35 300-pound-gorilla executives in the room — is Ground Rules.

I pre-publish a prepared list of ground rules to attendees, and also bring it on a flip chart into the meeting and hang it on the wall. The rules typically include:

— Start/end the meeting on time

— No interruptions

— No side conversations

— No phone calls/email in the meeting

— Everyone participates in brainstorming

— In dealing with conflict, we focus on the business choices, not on the people arguing for or against them

— We use a "parking lot" to capture ideas that are important to pursue, but not relevant to the work of this meeting.

— We leave the room with a clear record of decisions made and who is accountable for follow-up.At the start of the meeting, ask if there is anyone who is not willing to work by these rules, and if there are additional ground rules needed.

And then when the EVP of Bananas starts steamrolling the conversation, cut her off; point to the flip chart; and say, "Cheetah, we have a rule about no interruptions. I'd like Tarzan to finish what he was saying and then I'll turn it over to you."

Cheetah won't like it. But 95% of the time, she'll do it. The other 5% of the time, you have to be willing to enlist the group's help to enforce the rules. That goes something like: "Okay, we all agreed to these rules. Cheetah has just said that she doesn't want to be bound by them. Does the rest of the group agree that these rules should be ditched? In my experience as a facilitator, if you're not willing to have rules for meetings, you'll have less effective meetings. That's up to you. What would you like to do?"

And then abide by the group's decision. Which will usually be "well… I think we should have rules… " (with covert looks at Cheetah, who will be pissed but basically powerless, unless she is real asshole).

I can already hear the howls of disbelieving laughter from folks, along the lines of "if only"… but I've done this plenty of times, always with success and never with any kind of retribution beyond the occasional "oh, right, PROCESS!" sneers.

The thing is, people will generally follow the most effective behavior that's modeled for them. Ground rules help you model the behavior and give you an objective reference point for calling out rudeness/ineffective behavior.

Most workplace assholes get away with it because no one stops them. Having an objective tool agreed on by the group can really help.

Kelley, thanks for taking the time write such a lovely and thoughtful comment.

-

What Should a New Boss Do the First Few Weeks?

One of my former students wrote a great email this morning, and although I fumbled to give him a few answers, I felt like I didn't give him the answer he deserved. He has been working the past couple years as an "individual contributor" at a professional services firm. I know him pretty well, as he was a student in a couple intense d.school classes I taught and was also my teaching assistant in another class. He is very smart and very hard working. But he is about to start a new role from him: As the boss of a four-person team.

Here is his question:

"I am a bit

nervous as I will be leading a team of four, all more senior than myself in

both age and tenure. And to be honest, I'm not sure what to do or say

over the first few weeks. I don't believe I'll be an asshole, or have a

power trip, but am more concerned about making the right impression off the

bat. Got any nuggets of wisdom?"I wonder if any of you can help this new boss. How does he make a good impression — and I would add — set the stage so that they not only like him, but also do great work?

-

Do You End Meetings On Time?

I realize that there are times when true crises arise, decisions need to be made, urgent action need to be taken, and so on –so a group leader must keep a meeting running after the scheduled ending time. But I have been in a number of situations over the years– with meetings inside and outside Stanford, in classes, conferences, and dozens of other situations — where the meeting stretches on well-past the appointed ending time for no good reason. I also occasionally hear stories from my kids about how they are late to their next class –and get in trouble — because one of their teachers insists on holding them in class after the bell rings for some ridiculous reason.

Keeping people later that scheduled is, to me, rude because it means they are often late to their next meetings, late for after work activities (I recall a meeting that made me late to one of my kid's plays years ago), and it infringes on their individual productivity.

There are at least four reasons that this seems to happen, none of which are very flattering to leaders:

1. The Leader is Clueless. This is when the leader doesn't realize that it is well past ending time or doesn't know when the meeting actually ends. I am disorganized enough that I have kept students later than I should because I didn't know the ending time, but when it happens, it is clearly a failure of my management skills. Those of us who lead routine meetings have an obligation to know when they are supposed to end, and to stick to it.

2. The Leader Lacks the Courage — or Perhaps the Power — to Stop Overbearing Blabbermouths. I've seen this happen when a leader with good intentions realizes that it is past the appointed ending time, but can't quite bring him or herself to stop one or more blabbermouths from droning on and on. In some of the worst cases, the blabbermouths KNOW that they are holding everyone hostage, the leader tries to stop them, but they keep insisting that on talking and talking — in other words, they, rather than the leader, is suffering from an exaggerated sense of self-importance.3. The Leader has an Exaggerated Sense of Self-Importance. Unfortunately, this happens all too often. Although the meeting or conference is about a routine or trivial matter, the leader believes that he or she is such an important person that nothing else in the other participants' lives — their next meeting, their individual work, their friends and families — could possibly be as important as ME.

4. The Leader is Doing it as a Power Move. This is related to 3, but is a more vile form. It is when the leader keeps people late to show that he or she CAN –to demonstrate he or she has the power to screw-up your next meeting, undermine your other work, make you late to see your friends, lovers, and families, and generally run roughshod over you. By the way, research on commitment suggests that if you continually allow your boss to run roughshod over you in this and other ways, and you believe you are doing it voluntarily, your commitment to the leader will increase: to reduce cognitive dissonance, you will need to explain two thoughts to yourself, "I am screwing-up the rest of my life as I wait for this meeting to end" and "I am doing this by choice." A good way to reduce this dissonance is to convince yourself that the leader and the group are more important than everything else — even if they are not.If you are a leader, I would ask you to start thinking about if you have a habit of keeping people late. Why are you doing it? Is it really worth screwing up people's lives, and in the case of people who have individual work to do, really worth stealing time from their individual projects to make one more point?

If you are constantly subjected to such treatment, try walking-out. Even better, do a little "pre-work" with others who feel similarly oppressed and all work out together — that is a great way to show an overbearing boss that he or she can't push you around. This may be impolite as well, but I think that leaders who continually disrespect people in this way deserve to get the message.

I also think that there is something about the way our schools socialize us that brainwashes us to believe we have to stay in our seats and can't get-up until the teacher dismisses us — indeed, this is so ingrained in many of us that we don't even THINK about getting-up. There are many times in adult life when you can just walk out, and you and everyone else might be better for it.Views: Defending Collegiality – Inside Higher Ed

P.S. As I wrote when discussing Microcosmographia Academia a few months back, if you really want to please people at a meeting –whether you are the leader or not — move for early dismissal! As F.M. Cornford put it so well "Motions for adjournment, made less than

fifteen minutes before tea-time or at any subsequent moment, are always

carried."Upadate: Thanks to Chris Young over at The Rainmaker group for picking this as one of his Fab 5 picks of the week.

-

Which One of My Children Should I Stop Feeding?

I heard this line from a manager I've known for many years. He was describing how painful layoffs had been for him at his company, and how that was his gut reaction to being asked who should be let go. He believed layoffs were necessary for "feeding everyone else," but it reminded me how tough these times are on everyone. Even the most compassionate and caring companies are feeling compelled to cut people — including the top rated companies on Fortune's Best Place to Work survey: both Google (top in 2008) and NetApp (top in 2009) have done layoffs in recent months.

-

Information Sharing in Teams: Impediments To Overcome

The Journal of Applied Psychology just published a "Meta-Analysis" on the links between information sharing and team performance. This method entails using quantitative analysis to uncover patterns across large numbers of studies — in this case, 72 studies of nearly 5000 groups. The overall findings aren't a surprise, that groups that engage in more information sharing enjoy better performance, cohesion, knowledge integration, and satisfaction with decisions made — but given the best bosses are usually masters of the obvious first and foremost, this is useful reminder that getting people to feel safe enough and to have enough time to share their knowledge is worth the trouble.

There was another twist, however, that bosses ought to devote a bit more attention to, a pair of red flags. The first was that the more distributed the information (the more different places it is in, including spread among different people,locations and departments), the less sharing there was and, perhaps most troubling, the more heterogeneity there was (i.e., the more diversity there was on things ranging from gender, to race, to age, to professional background) the less likely they were to share information.

The upshot for people leading teams and in teams is that you've got to remember that in the situations when you need to share information most — both in terms of avoiding pitfalls and reaching top performance –are times when there are strong impediments. To be more concrete, if information is spread around different people and places, and if people have different backgrounds, you really need to work in getting them to trust each other, take the others' perspective, and listen carefully to each other.

I see this in the best Stanford student teams. Last year, we did project for a major airline to increase the customer service experience at a large airline. The three person team was about as different as you could construct in a three person team (except all were under 35). An African American female MBA, A female Romanian doctoral student in chemistry, and a male Ph.D student in engineering. They went through a brief period of getting to know each other, but once they got past their differences, the speed at which they started talking, listening, and brainstorming, and combining knowledge was breathtaking — and indeed, they came-up with implemented a prototype to improve the experience of retrieving luggage that was implemented a few months later. The worst groups, however, are composed of people who, say, act like the most stereotypical of MBAs, engineers, and designers, don't listen to each other and don't teach each other. On average, though, I am impressed that, if you create conditions were the differences are raised and people have time to work together on short projects to learn each others strengths and weaknesses, teams that have the most diverse members do the best work — and to add a note of warning, the worst work too, because if they never get past their differences (as people open-up more slowly to others who are "different"), they are the worst.

So, having the information spread around a team and having diverse team members is a high magnitudes situation — it brings out the best and worst in teams, and as a boss, part of your job is to make sure it brings out the best.

Finally, the weirdest twist is that groups that tended to TALK more, shared LESS information. My guess is that this happens because some groups are prone to having norms and a status game where the goal is steal the air time and display dominance, rather than to listen to each other, combine what was said, and act. This is especially true in occupations where people aren't paid to talk, but to do stuff. I recall a great old study of British string quartets where the best groups would talk and fight less, and play more. They were more effective partly because you can't fight as easily when you are playing and partly because disagreements about what to play are worked out best while testing what will work, not arguing over it.

P.S. I found this article described at BPS Research Digest. Here is the reference:Mesmer-Magnus, J., & DeChurch, L. (2009). Information sharing and team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94 (2), 535-546.

Here is the study of quartets: Murnighan,

J. K. and Conlon, D. J. (1991). The dynamics of intense work groups:

A study of British string quartets. Administrative Science Quarterly,

36, 165-186 -

Preview of Peter Principle Foreword

As I wrote yesterday, it was A Big Day for Incompetence as two things came out about the 40th Anniversary Edition of The Peter Principle. Yesterday, I talked about the INC interview with Leigh Buchanan. Today, I will focus on the Foreword, which I wrote for the book. The book is actually not officially out, but BusinessWeek has published the entire Foreword online. You can get it here. To give you taste, here is the opening of my take on "Dr. Peter's Useful and Hilarious Classic."

The Peter Principle came as a revelation to my father,

Lewis Sutton. He ran a little company in San Francisco called Oceanic

Marine that sold furniture and related equipment, which he installed on

United States Navy ships. His livelihood depended on U.S. government

bureaucrats and shipyard managers, who often made him miserable. I grew

up listening to his tirades about how these "overpaid idiots" insisted

that he produce and procure poorly designed furnishings, how they could

barely do their jobs, and how pathetically lazy they were. To make

matters worse, senior government officials produced an onslaught of

absurd procedures that required him to jump through an ever-expanding

maze of administrative hoops—which wasted his time, drove up his costs,

and made him crazy. He concluded: "The morons at the top must be paid

to waste as much taxpayer money as possible."My father loved The Peter Principle because it

explained why life could be so maddening—and why everyone around you

seems, or is doomed to become, incompetent. The people who ran the U.S.

Navy and the shipyards didn't intend to do such lousy work. They were

simply victims of Dr. Peter's immutable principle. They had been

promoted inevitably, maddeningly, absurdly to their "level of

incompetence." Dr. Peter also taught my father not to expect the few

competent bureaucrats and managers he encountered to stick around for

long, as they would soon be promoted to a job that they were unable to

perform properly. Dr. Peter even showed that such incompetence had

pervaded my dad's business for hundreds of years. The book quotes a

report from 1684 about the British Navy: "The naval administration was

a prodigy of wastefulness, corruption, ignorance, and indolence…no

estimate could be trusted…no contract was performed…no check was

enforced."My dad took special delight in the pseudoscientific jargon that Dr.

Peter invented to describe the weird and wasteful behaviors displayed

by those languishing at their level of incompetence. Peter gave absurd

and comedic names to the tragic realities of working life. The root of

the entire book, the condition of incompetence that Peter called "Final

Placement Syndrome," leads some to develop "Abnormal Tabulology" (an

"unusual and highly significant arrangement of his desk"). This

pathology is manifested, for example, in "Tabulatory Gigantism" (an

obsession with having a bigger desk than his colleagues) ……. (see the rest here)P.S. Here is a story about 28,000 UC San Diego students who accidentally got congratulatory emails and letters indicating they had been admitted — when they were actually rejected. The Peter Principle lives!

-

A Big Day for Incompetence

That is what the title of the email from Barbara Teszler of HarperCollins said — and this isn't an April Fool's joke (well, if it is a joke, it applies to every other day too). BusinessWeek online published a sneak preview of the new foreword I wrote to 40th Anniversary edition of The Peter Principle (I will talk about the Foreword tomorrow) and INC Magazine published an interview I did with them on the book called The Peter Principle Lives On. INC editor Leigh Buchanan did a masterful job of organizing my distracted ranting into a fun time. Note how most of the questions are better than the answers!

I especially like this Q and A between Leigh and me:

Question: "Competent leadership" doesn't exactly inspire awe. Leadership is supposed to be exalted, and competent smacks of low expectations. Maybe we should rehabilitate the word. In Search of Competence! Where's Tom Peters when you need him?

Answer: [Management professor] Jim March argues that simple competence —

having people who are willing and able to do their jobs — is what

really makes organizations run. Leaders don't matter that much. They

are like light bulbs: You've just got to find one that works.Note I have already blogged about simple competence, and have a BusinessWeek opinion piece coming out next week called "In Praise of Simple Competence," which was partly inspired by the Peter Principle, and of course Jim March and the weird times we are in too.

-

Vending machines, The ET Game Story, and Atari

Walter wrote such a fascinating comment on the Interesting Shoes post that I thought you should all see it:

"I worked with someone who survived three layoffs at Atari. The remaining engineers figured out that they brought in smaller vending machines before the layoff. Apparently it was more important to tell the snack vendor than to tell the employees."

Atari's ups and downs were amazing. When I returned to the San Francisco Bay Area after five years in Michigan to take my job at Stanford in the early 1980's, one of the first papers I worked on was about downsizing at Atari. It was really a crazy place. I have to dig-up our paper, as I have not read it in years, but — besides the fact that they did just an awful job dealing with downsizing — the stories were just wild. It was a real sex and drugs driven kind of place. And the craziest story I remember was of the ET game. The basic outline is that Atari paid a fortune to do a game linked to movie for the VCS 2600 (the device they sold millions of, which played video games on your TV), they made the game in a huge rush (the people we interviewed always alleged that Ray Kassar, then CEO, was constantly bringing the designers drugs and women to keep them motivated), then Kassar was so enthusiastic about the game that they went for a huge first run (I recall 8 million), and then the initial sales were good because of the ET film.

But when kids brought the ET game home to play, they found it sucked as a game (quality always matters), so sales stopped and returns skyrocketed. Then, as at least five interviewees (including senior executives)told us, since no one bought them, they put hundreds of thousands in landfill, and drove bulldozers over them to smash them. But they all didn't get smashed, and local kids found them, and started bringing then into stores to exchange them for games they actually wanted. So the solution was to finally put concrete over them so the kids couldn't get to them.

This story was not only entertaining, the reason that executives thought it was so crucial was, until that moment, Atari was on a straight ride up and up, and the feeling was that they were so cool and so smart that they could no wrong. This incident played a big role in shattering that delusion — and revealing their arrogance and excess. Then came the badly managed layoffs, which I think happened in part because executives were in such a state of shock and were actually quite embarrassed by the whole mess.

Here is the reference for the paper:

Sutton,R.I.

Eisenhardt, K.M., & Jucker, J.V.

(1986) Managing organizational

decline: Lessons from Atari. Organizational Dynamics, 14: 17-29.P.S P.S. Wikipedia reports that Kassar was not responsible foe the E.T. game, the deal was made a Warner executive. Which may be true, and I am also sure that many of the myths around it were false — it was the spreading and telling of the story that was interesting. And objectively, whatever details were true or false, all agree that this game was the turning point where the went for a company where everything they touched turn to gold, to one where everything went wrong.