One of the hallmarks of creative people, teams, and organizations is that they accept failure and view it as an essential part of their life. That is why, as Diego Rodriguez and I like to say, failure sucks but instructs. There is growing evidence that people learn more from failure than from success — although an important caveat is that people seem to learn the most when they review both successes and failures that occurred during an experience. Regardless, whether it is venture capitalists, pharmaceutical researchers, or product designers that you are talking about, there is always a high failure rate in creative work. I used the the example of toy design at IDEO in Weird Ideas That Work. Note that Brendan Boyle, the star of this story, is still at IDEO and they still design toys and other products (and experiences) for kids, but Skyline has now been integrated into the rest of the company.

Here is what I wrote back in 2001:

Brendan Boyle is

founder and head of Skyline, a group of toy designers at IDEO in Palo Alto, California Boyle provides compelling evidence that

innovative companies need a wide range of ideas and that success requires a

high failure rate. Boyle and his fellow designers keep careful track of

the ideas they generate in brainstorming sessions and informal conversations,

and that just pop into their heads. Skyline keeps close tabs on its

ideas because it sells and licenses ideas for toys that are made, distributed,

and marketed by big companies like Mattel and Fisher-Price.

Boyle showed me a spreadsheet indicating that, in 1998, Skyline (which had

fewer than 10 employees) generated about 4000 ideas for new toys. Of

these 4,000 ideas, 230 were thought to be promising enough to develop into a

nice drawing or working prototype. Of these 230, 12 were ultimately

sold. This “yield” rate is only about 1/3 of 1% of total ideas and 5% of

ideas that were thought to have potential. Boyle pointed out that

the success rate is probably even worse than it looks because some toys that

are bought never make it to market, and of those that do, only a small

percentage reap large sales and profits. As Boyle

says, “You can’t get any good new ideas without having a lot of dumb, lousy,

and crazy ones. Nobody in my business is very good at guessing which are

a waste of time and which will be the next Furby.”

I use this example a lot in talks on innovation because Brendan was kind enough and brave enough to give me information about his team's failure rate, but unfortunately — although I am always asking for this kind of information — most people decline to give it to me (sometimes they say it is propriety information, other times it is clear they just don't want to have information out there about their failures). But I just accidentally ran into another example on the radio show, "This American Life," in an episode called "Tough Room," which aired in February. Check out this podcast, notably "Act One: Make 'em Laff," which is about the creative process at The Onion, the famous fake news organization. It describes and has audio of the sessions where the writers pitch headlines for Onion stories to their fellow writers. As host Ira Glass says, this is a tough room where most ideas being shot down immediately and, even those that strike people as funny at first usually don't make it into print. According to the story, to get the 18 headlines they need for each week's edition, the writers usually propose about 600. This is actually a higher success rate than IDEO's toy group (about 3% survive), but printing a bad story is a lot cheaper than launching a bad product. I found the other nuances to be fascinating too — especially the constructive conflict and criticism in the group and the tensions between veterans and newcomers.

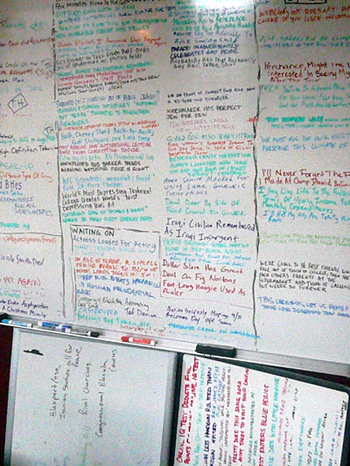

Also, I found the above picture of the white board with lists of possible future Onion stories on the This American Life website — look at all those ideas, that is what creativity looks like.

P.S. As you may recall, The Onion ran this story mocking researchers who discovered that assholes are bad for employee morale, which sure sounds like a parody of The No Asshole Rule to me (at least I hope so).